How To Draw Environmental Concept Art

Terminal Updated on May 27, 2021

This article has been written for high school art students who are working upon a critical study of art, sketchbook annotation or an essay-based artist report. Information technology contains a list of questions to guide students through the process of analyzing visual textile of whatsoever kind, including drawing, painting, mixed media, graphic design, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, photography, textiles, way and and then on (the word 'artwork' in this article is all-encompassing). The questions include a wide range of specialist art terms, prompting students to utilize subject-specific vocabulary in their responses. Information technology combines advice from fine art analysis textbooks as well as from loftier school art teachers who have outset-mitt experience educational activity these concepts to students.

COPYRIGHT Annotation: This material is bachelor as a printable art analysis PDF handout. This may be used complimentary of charge in a classroom state of affairs. To share this material with others, please use the social media buttons at the bottom of this folio. Copying, sharing, uploading or distributing this article (or the PDF) in any other style is not permitted.

Why practice we study art?

Almost all loftier school art students carry out critical analysis of creative person work, in conjunction with creating practical work. Looking critically at the piece of work of others allows students to sympathize compositional devices and then explore these in their own art. This is one of the best ways for students to learn.

Instructors who assign formal analyses want you to look—and look carefully. Think of the object as a series of decisions that an creative person made. Your job is to effigy out and describe, explicate, and interpret those decisions and why the creative person may accept made them. – The Writing Centre, Academy of North Carolina at Chapel Colina10

Art analysis tips

- 'I like this' or 'I don't like this' without any farther explanation or justification is not analysis. Personal opinions must be supported with caption, evidence or justification.

- 'Analysis of artwork' does non hateful 'description of artwork'. To gain high marks, students must move across stating the obvious and add together perceptive, personal insight. Students should demonstrate higher club thinking – the ability to analyse, evaluate and synthesize data and ideas. For example, if colour has been used to create strong contrasts in certain areas of an artwork, students might follow this ascertainment with a thoughtful assumption nigh why this is the example – perhaps a deliberate effort by the artist to draw attention to a focal point, helping to convey thematic ideas.

Although description is an of import part of a formal analysis, description is non enough on its own. Y'all must introduce and contextualize your descriptions of the formal elements of the work so the reader understands how each element influences the piece of work'southward overall issue on the viewer. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing Near Fine arttwo

- Comprehend a range of dissimilar visual elements and design principles. It is common for students to go experts at writing virtually one or ii elements of limerick, while neglecting everything else – for example, only focusing upon the employ of color in every artwork studied. This results in a narrow, repetitive and incomplete assay of the artwork. Students should ensure that they cover a broad range of art elements and design principles, as well as address context and pregnant, where required. The questions beneath are designed to ensure that students comprehend a broad range of relevant topics inside their analysis.

- Write alongside the artwork discussed. In nigh all cases, written analysis should exist presented alongside the work discussed, so that it is clear which artwork comments refer to. This makes it easier for examiners to follow and evaluate the writing.

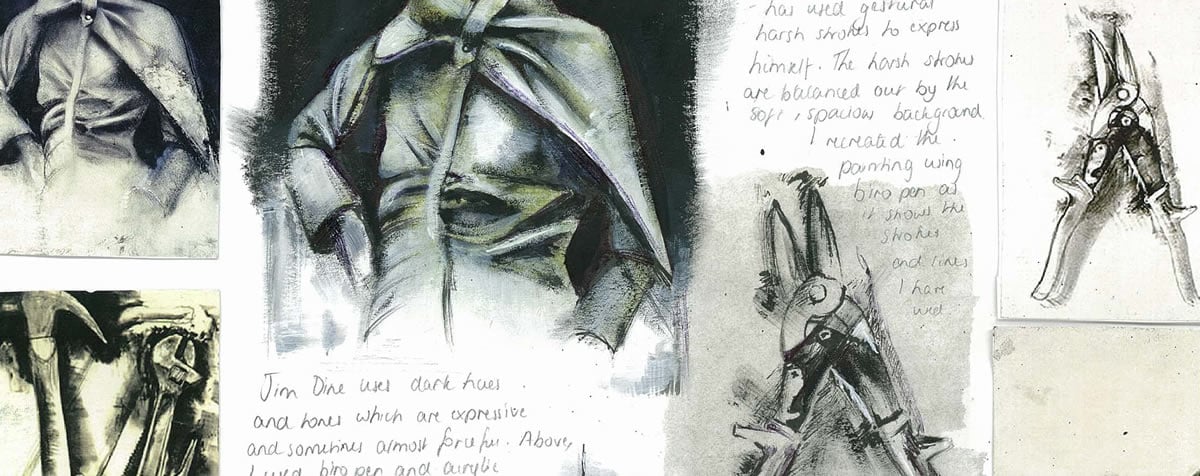

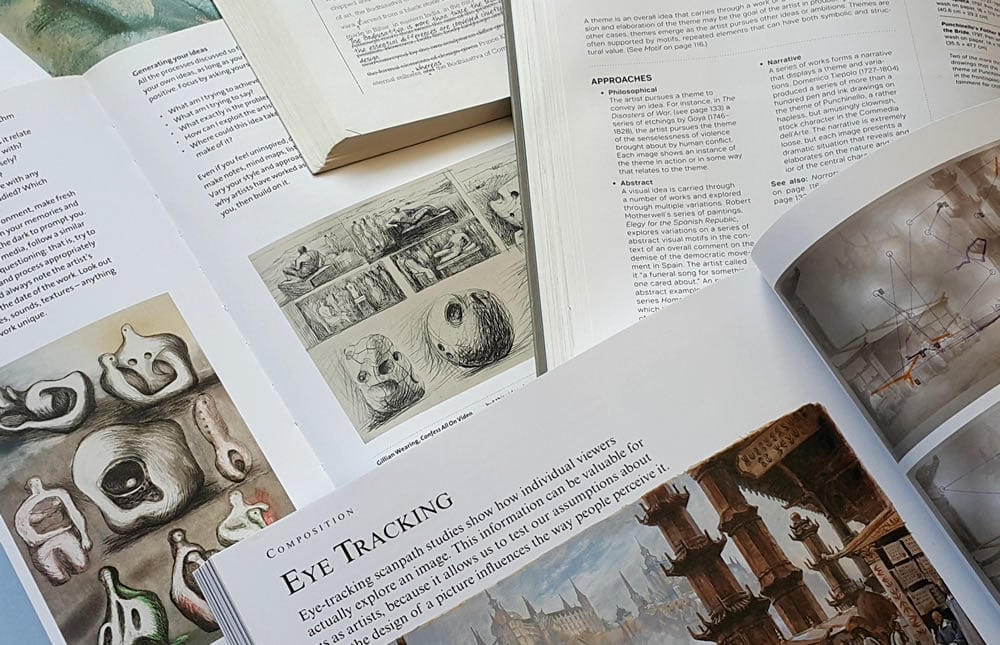

- Support writing with visual analysis. It is almost e'er helpful for loftier school students to support written material with sketches, drawings and diagrams that help the student sympathize and analyse the piece of art. This might include composition sketches; diagrams showing the primary structure of an artwork; detailed enlargements of small sections; experiments imitating utilize of media or technique; or illustrations overlaid with arrows showing leading lines and and then on. Visual investigation of this sort plays an important role in many artist studies.

Making sketches or drawings from works of art is the traditional, centuries-one-time mode that artists take learned from each other. In doing this, you lot will appoint with a work and an artist's approach even if you previously knew zilch virtually it. If possible do this whenever you can, not from a postcard, the internet or a picture show in a book, only from the actual piece of work itself. This is useful because it forces you to look closely at the work and to consider elements you might not have noticed before. – Susie Hodge, How to Look at Fine art7

Finally, when writing about fine art, students should communicate with clarity; demonstrate subject-specific noesis; use correct terminology; generate personal responses; and reference all content and ideas sourced from others. This is explained in more detail in our article about high school sketchbooks.

What should students write about?

Although each aspect of composition is treated separately in the questions below, students should consider the human relationship between visual elements (line, shape, grade, value/tone, color/hue, texture/surface, infinite) and how these interact to course design principles (such as unity, variety, emphasis, dominance, balance, symmetry, harmony, movement, contrast, rhythm, blueprint, scale, proportion) to communicate meaning.

As complex as works of art typically are, in that location are really simply iii general categories of statements i can make most them. A statement addresses form, content or context (or their diverse interrelations). – Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia5

…a formal analysis – the result of looking closely – is an analysis of the form that the artist produces; that is, an analysis of the work of art, which is made up of such things as line, shape, color, texture, mass, composition. These things requite the stone or sail its form, its expression, its content, its meaning. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Fine art2

This video by Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Naraelle Hohensee provides an first-class example of how to analyse a piece of art (information technology is of import to note that this video is an instance of 'formal analysis' and doesn't include contextual assay, which is also required by many high school art test boards, in addition to the formal assay illustrated here):

Composition analysis: a list of questions

The questions beneath are designed to facilitate direct engagement with an artwork and to encourage a breadth and depth of understanding of the artwork studied. They are intended to prompt higher order thinking and to assistance students go far at well-reasoned analysis.

It is not expected that students answer every question (doing so would result in responses that are excessively long, repetitious or formulaic); rather, students should focus upon areas that are near helpful and relevant for the artwork studied (for example, some questions are appropriate for analyzing a painting, only non a sculpture). The words provided every bit examples are intended to help students think nigh advisable vocabulary to use when discussing a item topic. Definitions of more complex words have been provided.

Students should not endeavour to copy out questions and then respond them; rather the questions should be considered a starting point for writing bullet pointed notation or sentences in paragraph form.

CONTENT, CONTEXT AND MEANING

Bailiwick thing / themes / issues / narratives / stories / ideas

There tin can be different, competing, and contradictory interpretations of the aforementioned artwork.

An artwork is not necessarily about what the artist wanted it to exist about. – Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporaryhalf-dozen

Our interest in the painting grows only when we forget its title and have an interest in the things that information technology does not mention…" – Françoise Barbe-Gall, How to Expect at a Painting8

- Does the artwork fall within an established genre (i.due east. historical; mythical; religious; portraiture; mural; still life; fantasy; architectural)?

- Are there any recognisable objects, places or scenes? How are these presented (i.east. idealized; realistic; indistinct; hidden; distorted; exaggerated; stylized; reflected; reduced to simplified/minimalist form; primitive; abstracted; curtained; suggested; blurred or focused)?

- Take people been included? What tin we tell about them (i.e. identity; age; attire; profession; cultural connections; health; family relationships; wealth; mood/expression)? What can we learn from their pose (i.e. frontal; profile; partly turned; body linguistic communication)? Where are they looking (i.e. direct eye contact with viewer; downcast; interested in other subjects inside the artwork)? Tin can we work out relationships between figures from the way they are posed?

What exercise the clothing, furnishings, accessories (horses, swords, dogs, clocks, business ledgers and then forth), background, angle of the head or posture of the caput and body, direction of the gaze, and facial expression contribute to our sense of the figure's social identity (monarch, clergyman, bays wife) and personality (intense, cool, inviting)? – Sylvan Barnet, A Brusk Guide to Writing About Art2

- What props and important details are included (drapery; costumes; adornment; architectural elements; emblems; logos; motifs)? How do aspects of setting support the main subject? What is the effect of including these items within the organisation (visual unity; connections between dissimilar parts of the artwork; directs attention; surprise; variety and visual interest; separates / divides / borders; transformation from one object to another; unexpected juxtaposition)?

If a waiter served you a whole fish and a scoop of chocolate ice cream on the aforementioned plate, your surprise might be acquired by the juxtaposition, or the side-by-side dissimilarity, of the ii foods. – Vocabulary.com

A motif is an chemical element in a composition or design that can exist used repeatedly for decorative, structural, or iconographic purposes. A motif can be representational or abstract, and it can be endowed with symbolic meaning. Motifs can exist repeated in multiple artworks and often recur throughout the life's piece of work of an private artist. – John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Fine art11

- Does the artwork communicate an action, narrative or story (i.east. historical event or illustrate a scene from a story)? Has the arrangement been embellished, ready up or contrived?

- Does the artwork explore motion? Do you gain a sense that parts of the artwork are well-nigh to change, topple or fall (i.e. tension; suspense)? Does the artwork capture objects in motion (i.e. multiple or sequential images; blurred edges; scene frozen mid-action; alive performance art; video art; kinetic art)?

- What kind of abstract elements are shown (i.e. bars; shapes; splashes; lines)? Accept these been derived from or inspired past realistic forms? Are they the result of spontaneous, accidental creation or careful, deliberate arrangement?

- Does the piece of work include the appropriation of work by other artists, such as within a parody or popular art? What effect does this have (i.due east. copyright concerns)?

Parody: mimicking the appearance and/or mode of something or someone, but with a twist for comic effect or disquisitional comment, as in Saturday Night Live'south political satires – Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia5

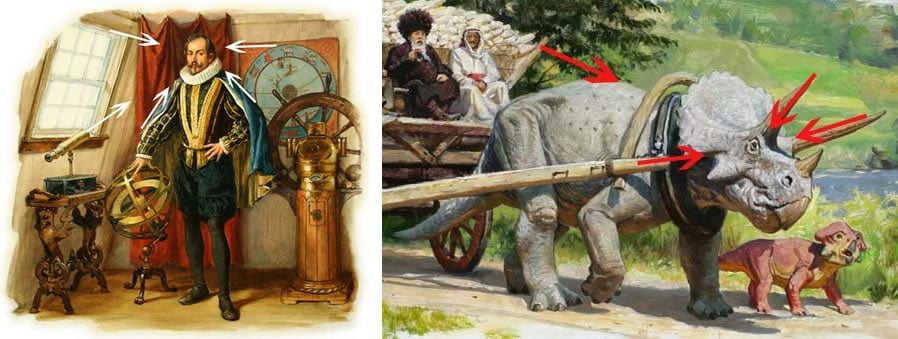

- Does the subject field obsess an instinctual response, such as items that are informative, shocking or threatening for humans (i.e. dangerous places; abnormally positioned items; human being faces; the gaze of people; motion; text)? Heap map tracking has demonstrated that these elements catch our attention, regardless of where they are positioned –James Gurney writes more about this fascinating topic.

- What kind of text has been used (i.e. font size; font weight; font family; stenciled; manus-drawn; computer-generated; printed)? What has influenced this option of text?

- Do key objects or images have symbolic value or provide a cue to significant? How does the artwork convey deeper, conceptual themes (i.eastward. allegory; iconographic elements; signs; metaphor; irony)?

Allegory is a device whereby abstract ideas can be communicated using images of the concrete world. Elements, whether figures or objects, in a painting or sculpture are endowed with symbolic meaning. Their relationships and interactions combine to create more complex meanings. – John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Artxi

An iconography is a detail range or organisation of types of epitome used past an artist or artists to convey particular meanings. For case in Christian religious painting there is an iconography of images such every bit the lamb which represents Christ, or the pigeon which represents the Holy Spirit. – Tate.org.uk

- What tone of voice does the artwork have (i.due east. deliberate; honest; autobiographical; obvious; direct; unflinching; confronting; subtle; ambiguous; uncertain; satirical; propagandistic)?

- What is your emotional response to the artwork? What is the overall mood (i.e positive; energetic; excitement; serious; sedate; peaceful; calm; melancholic; tense; uneasy; uplifting; foreboding; calm; turbulent)? Which subject matter choices help to communicate this mood (i.east. atmospheric condition and lighting conditions; color of objects and scenes)?

- Does the title change the way you interpret the piece of work?

- Were in that location whatever design constraints relating to the subject field matter or theme/due south (i.east. a sculpture commissioned to represent a specific subject, place or idea)?

- Are there thematic connections with your ain project? What can you learn from the way the artist has approached this subject?

Wider contexts

All art is in office well-nigh the globe in which it emerged. – Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Agreement the Contemporarysix

- Supported by research, can you place when, where and why the piece of work was created and its original intention or purpose (i.e. private sale; commissioned for a specific owner; commemorative; educational; promotional; illustrative; decorative; confrontational; useful or practical utility; advice; created in response to a pattern cursory; private viewing; public viewing)? In what manner has this background influenced the outcome (i.east. availability of tools, materials or time; expectations of the patron / audition)?

- Where is the place of construction or blueprint site and how does this influence the artwork (i.e. reflects local traditions, adroitness, or customs; complements surrounding designs; designed to accommodate weather weather / climate; built on historic site)? Was the artwork originally located somewhere unlike?

- Which events and surrounding environments accept influenced this work (i.e. natural events; social movements such as feminism; political events, economical situations, historic events, religious settings, cultural events)? What issue did these have?

- Is the work feature of an artistic style, movement or time period? Has it been influenced past trends, fashions or ideologies? How can you tell?

- Can you brand any relevant connections or comparisons with other artworks? Take other artists explored a similar subject area in a similar mode? Did this occur before or after this artwork was created?

- Tin can you lot make whatever relevant connections to other fields of study or expression (i.e. geography, mathematics, literature, moving picture, music, history or scientific discipline)?

- Which fundamental biographical details about the artist are relevant in understanding this artwork (upbringing and personal situation; family unit and relationships; psychological state; health and fitness; socioeconomic status; employment; ethnicity; civilization; gender; didactics, religion; interests, attitudes, values and beliefs)?

- Is this artwork function of a larger trunk of work? Is this typical of the piece of work the creative person is known for?

- How might your own upbringing, behavior and biases distort your estimation of the artwork? Does your ain response differ from the public response, that of the original audition and/orinterpretation past critics?

- How do these wider contexts compare to the contexts surrounding your own work?

COMPOSITION AND Course

Format

- What is the overall size, shape and orientation of the artwork (i.e. vertical, horizontal, portrait, landscape or square)? Has this format been influenced by applied considerations (i.east. availability of materials; display constraints; design brief restrictions; screen sizes; mutual aspect ratios in film or photography such as 4:3 or 2:3; or paper sizes such as A4, A3, A2, A1)?

- How do images fit within the frame (cropped; truncated; shown in full)? Why is this format advisable for the subject area thing?

- Are unlike parts of the artwork physically separate, such every bit within a diptych or triptych?

- Where are the boundaries of the artwork (i.due east. is the artwork self-contained; meaty; penetrating; sprawling)?

- Is the artwork site-specific or designed to be displayed beyond multiple locations or environments?

- Does the artwork have a stock-still, permanent format, or was itmodified, moved or adjusted over fourth dimension? What causes such changes (i.due east. atmospheric condition and exposure to the elements – melting, erosion, discoloration, decaying, wind movement, surface abrasion; structural failure – neat, breaking; impairment caused by unpredictable events, such every bit fire or vandalism; intentional movement, such as rotation or sensor response; intentional impermanence, such as an installation assembled for an exhibition and removed afterwards; viewer interaction; additions, renovations and restoration by subsequent artists or users; a project so expansive information technology takes years to construct)? How does this change affect the artwork? Are at that place stylistic variances between parts?

- How does the scale and format of the artwork relate to the environment where information technology is positioned, used, installed or hung (i.eastward. harmonious with landscape typography; sensitive to adjacent structures; imposing or dwarfed by environment; man scale)? Is the artwork designed to be viewed from one vantage point (i.east. front facing; viewed from below; approached from a main archway; gear up at human eye level) or many? Are images taken from the best angle?

- Would a similar format benefit your ain project? Why / why not?

Structure / layout

- Has the artwork been organised using a formal system of arrangement or mathematical proportion (i.e. dominion of thirds; golden ratio or spiral; grid format; geometric; dominant triangle; or circular composition) or is the arrangement less predictable (i.e. chaotic, random, accidental, fragmented, meandering, scattered; irregular or spontaneous)? How does this system of arrangement aid with the communication of ideas? Can y'all draw a diagram to bear witness the basic structure of the artwork?

- Tin you see a clear intention with alignment and positioning of parts inside the artwork (i.e. edges aligned; items spaced every bit; simple or complex organisation; overlapping, clustered or concentrated objects; dispersed, separate items; repetition of forms; items extending beyond the frame; frames inside frames; bordered perimeter or patterned edging; cleaved borders)? What effect exercise these visual devices take (i.east. imply hierarchy; help the viewer understand relationships between parts of artwork; create rhythm)?

- Does the artwork have a principal axis of symmetry (vertical, diagonal, horizontal)? Tin can yous locate a center of balance? Is the artwork symmetrical, asymmetrical (i.eastward. stable), radial, or intentionally unbalanced (i.due east. to create tension or unease)?

- Can you lot draw a diagram to illustrate emphasis and say-so (i.e. 'blocking in' mass, where the 'heavier' dominant forms appear in the composition)? Where are dominant items located within the frame?

- How do your optics move through the composition?

- Could your own artwork employ a similar organisational construction?

Line

- What types of linear mark-making are shown (thick; thin; curt; long; soft; bold; delicate; feathery; indistinct; faint; irregular; intermittent; freehand; ruled; mechanical; expressive; loose; blurred; dashing; cross-hatching; meandering; gestural, fluid; flowing; jagged; spiky; sharp)? What atmosphere, moods, emotions or ideas do these evoke?

- Are there any interrupted, suggested or unsaid lines (i.e. lines that can't literally exist seen, but the viewer'south brain connects the dots betwixt separate elements)?

- Where are the dominating lines in the composition and what is the effect of these? Can you lot overlay tracing paper upon an artwork to illustrate some of the important lines?

- Repeating lines: may simulate material qualities, texture, pattern or rhythm;

- Purlieus lines: may segment, carve up or split up unlike areas;

- Leading lines: may manipulate the viewer'south gaze, directing vision or atomic number 82 the centre to focal points (eye tracking studies point that our eyes bound from one bespeak of interest to another, rather than move smoothly or predictably along leading lines9. Lines may yet help to establish emphasis by 'pointing' towards sure items);

- Parallel lines: may create a sense of depth or movement through space inside a mural;

- Horizontal lines: may create a sense of stability and permanence;

- Vertical lines: may suggest height, reaching upwards or falling;

- Intersecting perpendicular lines: may suggest rigidity, strength;

- Abstract lines: may balance the composition, create dissimilarity or emphasis;

- Angular / diagonal lines: may suggest tension or unease;

- Chaotic lines: may advise a sense of agitation or panic;

- Underdrawing, construction lines or contour lines: describe form (learn more about contour lines in our article about line drawing);

- Curving / organic lines: may suggest nature, peace, movement or free energy.

- What is the relationship between line and three-dimensional form? Areoutlines used to ascertain form and edges?

- Would it be appropriate to use line in a similar mode inside your own artwork?

Shape and form

- Can you identify a ascendant visual linguistic communication within the shapes and forms shown (i.e. geometric; athwart; rectilinear; curvilinear; organic; natural; fragmented; distorted; free-flowing; varied; irregular; complex; minimal)? Why is this visual linguistic communication advisable?

- How are the edges of forms treated (i.e. do they fade away or blur at the edges, as if melting into the folio; ripped or torn; singled-out and hard-edged; or, in the words of James Gurney9, practise they 'deliquesce into sketchy lines, pigment strokes or drips')?

- Are at that place whatever three-dimensional forms or relief elements within the artwork, such every bit carved pieces, protruding or sculptural elements? How does this affect the viewing of the work from different angles?

- Is in that location a variety or repetition of shapes/forms? What effect does this have (i.east. repetition may reinforce ideas, balance limerick and/or create harmony / visual unity; multifariousness may create visual interest or overwhelm the viewer with anarchy)?

- How are shapes organised in relation to each other, or with the frame of the artwork (i.e. grouped; overlapping; repeated; echoed; fused edges; touching at tangents; contrasts in calibration or size; distracting or awkward junctions)?

- Are silhouettes (external edges of objects) considered?

All shapes have silhouettes, and vision research has shown that ane of the first tasks of perception is to be able to sort out the silhouette shapes of each of the elements in a scene. – James Gurney, Imaginative Realism9

- Are forms designed with ergonomics and human calibration in mind?

Ergonomics: an applied science concerned with designing and arranging things people use and so that the people and things interact nearly efficiently and safely – Merriam-webster.com

- Can you identify which forms are functional or structural, versus ornamental or decorative?

- Have any forms been disassembled, 'cut away' or exposed, such as a sectional drawing? What is the purpose of this (i.e. to explicate structure methods; communicate information; dramatic effect)?

- Would it be appropriate to use shape and form in a similar way inside your own artwork?

Value / tone / calorie-free

- Has a wide tonal range been used in the artwork (i.e. a broad range of darks, highlights and mid-tones) or is the tonal range limited (i.e. stake and faint; subdued; dull; heart-searching and night overall; stiff highlights and shadows, with little mid-tone values)? What is the effect of this?

- Where are the light sources within the artwork or scene? Is there a unmarried consistent low-cal source or multiple sources of light (sunshine; light bulbs; torches; lamps; luminous surfaces)? What is the upshot of these choices (i.due east. mimics natural lighting conditions at a sure fourth dimension of day or nighttime; figures lit from the side to analyze grade; contrasting background or spot-lighting used to accentuate a focal surface area; soft and diffused lighting used to mute contrasts and minimize harsh shadows; dappled lighting to signal sunshine broken by surrounding leaves; chiaroscuro used to exaggerate theatrical drama and impact; areas cloaked in darkness to minimize visual complexity; to enhance our understanding of narrative, mood or meaning)?

One of the most important ways in which artists can apply low-cal to achieve particular effects is in making stiff contrasts between lite and dark. This contrast is often described as chiaroscuro. – Matthew Treherne, Analysing Paintings, University of Leeds3

- Are representations of three-dimensional objects and figures flat or tonally modeled? How practise different tonal values change from one to the next (i.e. gentle, smoothen gradations; precipitous tonal bands)?

- Are there any unusual, reflective or transparent surfaces, mediums or materials which reflect or transmit light in a special mode?

- Has tone been used to help communicate atmospheric perspective (i.e. paler and bluer as objects get further away)?

- Are gallery or ecology light sources where the artwork is displayed fixed or fluctuating? Does the piece of work appear different when viewed at different times of mean solar day? How does this touch your interpretation of the piece of work?

- Are shadows depicted within the artwork? What is the effect of these shadows (i.e. anchors objects to the folio; creates the illusion of depth and space; creates dramatic contrasts)?

- Do sculptural protrusions or relief elements catch the light and/or create bandage shadows or pockets of shadow upon the artwork? How does this influence the viewer'due south feel?

- How has tone been used to help direct the viewer's attention to focal areas?

- Would information technology be appropriate to apply value / tone in a similar manner inside your own artwork? Why / why non?

Color / hue

- Can you view the true color of the artwork (i.e. are you viewing a low-quality reproduction or examining the artwork in poor lighting)?

- Whichcolor schemes take been used within the artwork (i.e. harmonious; complementary; primary; monochrome; earthy; warm; cool/cold)? Has the artist used a broad or limited color palette (i.eastward. variety or unity)? Which colors dominate?

- How would you describe the intensity of the colors (vibrant; vivid; brilliant; glowing; pure; saturated; stiff; irksome; muted; pale; subdued; bleached; diluted)?

- Are colors transparent or opaque? Can you see reflected color?

- Has color dissimilarity been used within the artwork (i.e. farthermost contrasts; juxtaposition of complementary colors; garish / clashing / jarring)? Are in that location any abrupt color changes or unexpected uses of color?

- What is the effect of these color choices (i.e. expressing symbolic or thematic ideas; descriptive or realistic depiction of local color; emphasizing focal areas; creating the illusion of aerial perspective; relationships with colors in surrounding environment; creating residuum; creating rhythm/pattern/repetition; unity and variety within the artwork; lack of colour places emphasis upon shape, detail and form)? What kind of atmosphere do these colors create?

Information technology is oft said that warm colors (red, orange, yellow) come up frontwards and produce a sense of excitement (yellow is said to suggest warmth and happiness, as in the smiley face), whereas cool colors (blue, green) recede and have a calming effect. Experiments, however, have proved inconclusive; the response to colour – despite clichés virtually seeing red or feeling blueish – is highly personal, highly cultural, highly varied. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Fine art2

- Would it be appropriate to utilize color in a similar manner within your own artwork?

Texture / surface / design

- Are there whatsoever interesting textural, tactile or surface qualities within the artwork (i.east. bumpy; grooved; indented; scratched; stressed; rough; polish; shiny; varnished; glassy; sleeky; polished; matte; sandy; grainy; gritted; leathery; spiky; silky)? How are these created (i.east. inherent qualities of materials; impasto mediums; sculptural materials; illusions or implied texture, such as cross-hatching; finely detailed and intricate areas; organic patterns such as leaf or pocket-sized stones; repeating patterns; ornamentation)?

- How are textural or patterned elements positioned and what issue does this accept (i.e. used intermittently to provide variety; repeating pattern creates rhythm; patterns cleaved create focal points; textured areas create visual links and unity between separate areas of the artwork; balance between detailed/textured areas and simpler areas; glossy surface creates a sense of luxury; faux of texture conveys information nearly a subject, i.e. softness of fur or strands of hair)?

- Would information technology be appropriate to utilize texture / surface in a similar style within your own artwork?

Space

- Is the pictorial space shallow or deep? How does the artwork create the illusion of depth (i.e. layering of foreground, middle-ground, background; overlapping of objects; utilise of shadows to ballast objects; positioning of items in relationship to the horizon line; linear perspective – acquire more about i point perspective hither; tonal modeling; relationships with adjacent objects and those in close proximity – including the human form – to create a sense of scale; spatial distortions or optical illusions; manipulating scale of objects to create 'surrealist' spaces where true scale is unknown)?

- Has an unusual viewpoint been used (i.e. worm's view; aerial view, looking out a window or through a doorway; a scene reflected in a mirror or shiny surface; looking through leaves; multiple viewpoints combined)? What is the effect of this viewpoint (i.e. allows certain parts of the scene to exist ascendant and overpowering or squashed, condensed and foreshortened; or suggests a narrative between two separate spaces; provides more information about a space than would normally be seen)?

- Is the emphasis upon mass or void? How densely arranged are components within the artwork or picture plane? What is the relationship betwixt object and surrounding infinite (i.e. compact / crowded / busy / densely populated, with little surrounding infinite; spacious; careful interplay between positive and negative infinite; objects clustered to create areas of visual interest)? What is the outcome of this (i.eastward. creates a sense of emptiness or isolation; business concern / visual ataxia creates a feeling of chaos or claustrophobia)?

- How does the artwork appoint with real infinite – in and effectually the artwork (i.due east. self-contained; closed off; eye contact with viewer; reaching outwards)? Is the viewer expected to move through the artwork? What is the relationship between interior and exterior infinite? What connections or contrasts occur between inside and out? Is it comprised of a series of separate or linked spaces?

- Would it be appropriate to utilize space in a similar fashion within your own artwork?

Use of media / materials

- What materials and mediums has the artwork been synthetic from? Take materials been concealed or presented deceptively (i.east. is there an authenticity / honesty of materials; are materials celebrated; is the structure visible or exposed)? Why were these mediums selected (weight; color; texture; size; forcefulness; flexibility; pliability; fragility; ease of employ; toll; cultural significance; durability; availability; accessibility)? Would other mediums have been advisable?

- Which skills, techniques, methods and processes were used (i.e. traditional; conventional; industrial; contemporary; innovative)? It is important to notation that the examiners exercise not want the regurgitation of long, technical processes, simply rather to encounter personal observations almost how processes effect and influence the artwork in question. Would replicating part of the artwork assist you lot gain a ameliorate agreement of the processes used?

- Has the artwork been congenital in layers or stages? For example:

- Painting: gesso ground > textured mediums > underdrawing > blocking in colors > defining course > final details;

- Architecture: brief > concepts > evolution > working drawings > foundations > structure > cladding > finishes;

- Graphic design: brief > concepts > development > Photoshop > proofing > press.

- How does the utilise of media help the artist to communicate ideas?

- Are these methods useful for your own project?

Finally, retrieve that these questions are a guide only and are intended to make you kickoff to think critically about the fine art you are studying and creating.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article you may also like our commodity about high schoolhouse sketchbooks (which includes a section near sketchbook notation). If yous are looking for more assistance with how to write an art analysis essay you may like our series nigh writing an creative person written report.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- A guide for Analyzing Works of Art; Sculpture and Painting, Durantas

- A Brusque Guide to Writing Most Fine art, Sylvan Barnet (Amazon affiliate link)

- Analysing Paintings, Matthew Treherne, University of Leeds

- Art and Art History Tips, The Academy of Vermont

- Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, Dr. Robert J. Belton, The University of British Columbia

- Criticizing Art: Agreement the Contemporary, Terry Barrett (Amazon affiliate link)

- How to Look at Fine art, Susie Hodge (Amazon affiliate link)

- How to Look at a Painting, Françoise Barbe-Gall

- Imaginative Realism, James Gurney (Amazon affiliate link)

- The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Loma

- Universal Principles of Art: 100 Primal Concepts for Understanding, Analyzing and Practicing Art, John A. Parks (Amazon affiliate link)

Amiria has been an Art & Design teacher and a Curriculum Co-ordinator for 7 years, responsible for the course blueprint and assessment of pupil work in two high-achieving Auckland schools. She has a Bachelor of Architectural Studies, Bachelor of Architecture (Starting time Class Honours) and a Graduate Diploma of Teaching. Amiria is a CIE Accredited Art & Design Coursework Assessor.

Source: https://www.studentartguide.com/articles/how-to-analyze-an-artwork

Posted by: gibsonthistalre98.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Draw Environmental Concept Art"

Post a Comment